Unearthing the Female Ingenuity

by Sousan Qadeer

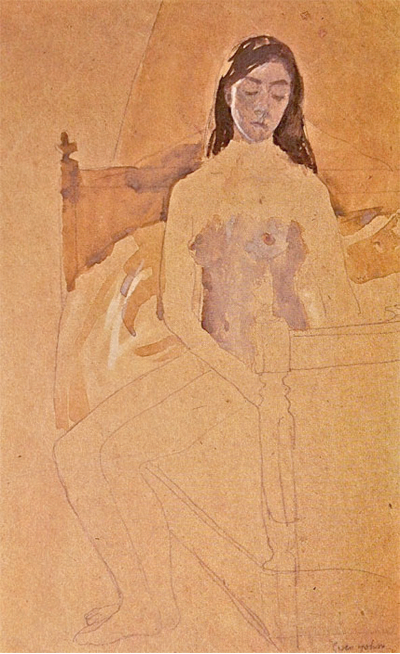

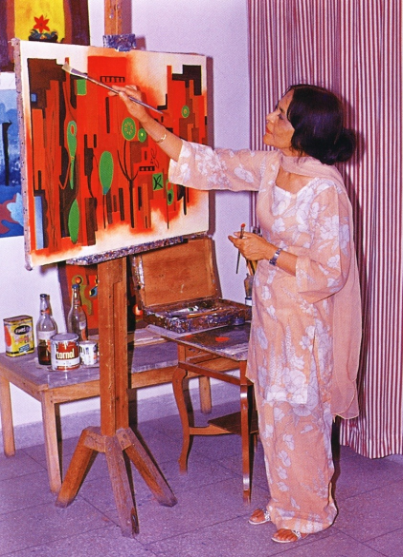

Shahzada’s work, exhibited in New York City in 1955.

Women are naturally creative. And even if they’re not, a little training in sewing, knitting or cooking would make them. Before the rise of feminism, in the West little girls were given art lessons at their homes as their brothers received training in more professional fields, such as sword fighting, archery and so on. The creative field has been associated with femininity for it has been labeled as something that you do in leisure. These “ornamental” tasks like painting and dancing were assigned to women so they wouldn't be judged for their idleness.

Certain stereotypes were associated with women who painted. They were often called bored housewives, with nothing much to do, painted bleak landscapes to hang on the wall of the family den. The sensational headline on the 1933 article written on Frida Kahlo, which says she “dabbles” in art, was thought to have been written by a male editor for a female reporter in a room full of male co-workers. To add insult to injury, this bias has existed in art history books as well for a long time.

In an androcentric society, the history of art has been a formidable opponent for women. It has failed to notice and observe women artists in such a way, that one does not simply say artists but this conviction of gender is a requisite when referring to women. To argue, history wasn't kind to women artists as well. Female artists lived under the umbrage of their contemporary male artists. If a woman wanted to show her talents or wanted to make a living to support herself, she would at the cost of her virtue, and on the condition that she would remain anonymous. In the 19th century, when women were accepted by art schools, they hardly made any career, instead, they accompanied famous artists who gave art lessons. Women taught art in their name while they made high art. Most women used to copy works of famous artists because they had value in the art market as opposed to their original work. Women were not allowed to study nude and for that matter, they were restrained from depicting biblical and allegorical subjects. And also that it was also considered the highest form of art which women were inherently incapable of attempting.

Gradually as women were admitted to art schools in France and Britain, they could not enjoy their studies in their entirety. As mentioned above, the nude figure was prohibited for women to study, because of unethical connotations attached to the nude body. Women were to stake their reputation for drawing a nude figure. The female nude was considered exclusively for the male gaze.

Women who were admitted to these art schools were charged much more than their male peers and were often daughters and relatives of established male artists who had made their name in the art industry, nevertheless, most of them couldn't make their careers in art themselves.

The male perspective was the only perspective considered when art history was written. Though it was not assessed as an obstacle to female ingenuity it was more of an absolute decision.

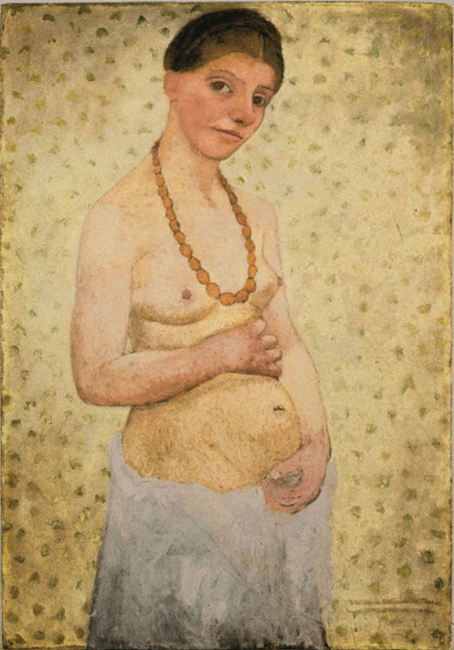

With the birth of feminism, the restraints of nude paintings by women gradually started to lift. Especially in Europe where artists like Gwen John (1876–1939) and Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), avidly painted nude self-portraits to depict themselves not just as artists but also as women who are artists. The styles in which these women depicted themselves were severed from the primitive conceptions of nude paintings and rather quite “modern”, both in technique and ideology.

Left: Self-portrait naked, sitting on a bed by Gwen John, 1908–1909.

Pencil and gouache, 25.5 x 16 cm. Private collection

Right: Self-portrait, age 30, sixth wedding day, 25th May, 1906 by Paula

Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907),1906.

Oil on cardboard, 101.8 cm x 70.2 cm,

Paula Modersohn-Becker Foundation, Bremen

Even with this new hope, distressing matters of female artist’s unemployment persisted. These women were formally trained as artists, but even then some of them failed to get employment or get commissions thus given no choice but to model as nude for male artists.

Whereas in America, women artists took advantage of the feminist movement to showcase gender inequality in their works rather than attending marches and parades. Women artists were battling gender bias extrovertly as opposed to women writers who adopted pseudonyms as a way to disguise themselves. Women artists, sculptors in particular soared, in terms of snatching commissions from men right under their noses.

The second feminist movement in the USA began around the 1970’s with protest signs and activism. Women also started to get appointed as gallery runners. There were several organizations too, which brought a lot of attention but sadly were not properly documented in New York, where most of these organizations were situated. However, the West Coasts did a better job of preserving the documents that were responsible for the great wave of feminism in art.

Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, was more of a question that was asked, not only targeting the men, who have been insidiously subsiding women from art history but also inciting women to finally break this perpetual silence. This essay was followed by an exhibition, which Nochlin curated with the assistance of Ann Sutherland Harris, named Women Artists 1550-1950, featuring the works of “forgotten” female artists from Europe and North America, which have been discredited for over 400 years. This exhibition was the culmination of the feminist art movement and served as a gateway for female art historians and curators to exhume the female ingenuity, and to bring them in the limelight.

Delistraty argues that the female genius is rather separated from the “genius” or so we have been told through art history, revised and recorded by men exclusively. The term, “genius artist” has been coined for privileged men only. Women, queers and people of color can be considered geniuses but should be labeled to their gender, sexual orientation or ethnicity. Sexual orientation, however, is another matter for discussion. Whenever we talk about old masters such as Michelangelo and Carravagio, we tend to mention their sexual preferences as well to understand their art more closely. The same applies to women. It is somehow important to mention that women are also capable of achieving greatness but only under the banner of their gender.

Women artists in the 16th and 17th-century art scene were depicting family portraiture in their artistic practice. These family portraits were of wives, daughters and sisters, represented as dependents on the men of the family. The artist’s signature was also not attributed to women painters and existed only for male artistic practice. The bystander artworks were also restricted for women artists as they were prohibited from depicting crowd scenes.

Women artists in the 16th century were to sacrifice their careers if they ever hoped to get married. This notion of educated women not wanting to get married is still applicable to this day but it was not questioned as often as it is now. Notwithstanding the argument, numerous Netherlandish women of the 16th century were married and were thriving as artists as well. One of these women, Anna Francisca de Bruyns (1604/5–1656), was born into an upper-class family for which she had access to private tutelage in art as opposed to women who were not privileged. Her retrieval of the female genius has been made possible because of her son who published an autobiography of her after her death. The book consisted of several of her artworks.

Anna Francisca de Bruyns, Richly Dressed Woman (possibly a self-portrait), inscribed on the back: ‘A.F. de Bruyns 1633’, present location unknown

Among the women portrait painters of the 16th century, Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625) is perhaps the one who was credited the most in art history after her death. Many art historians and art critics have compared her works to Titian’s as they were both contemporaries. Anguissola was appointed to King Philip II’s court to serve as a portrait painter. This adulation inspired more women of her time to learn painting.

Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of the Artist's Sisters Playing Chess.

Poznań, Muzeum Narodowe

As women, artists were often sexualized by their peers and art history. Similar is the case for Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652), whose art, due to a misfortunate event of unconsented sex in her teens, is often sexualized for its content. Gentileschi was labeled as a seductress at that time, whereas now she is lauded as a heroine and a feminist. Despite all the obstacles, Gentileschi became the first woman to be a member of Accademia di Arte del Disegno in Florence.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as La Pittura.

London, Kensington Palace, Collection of Her Majesty the Queen.

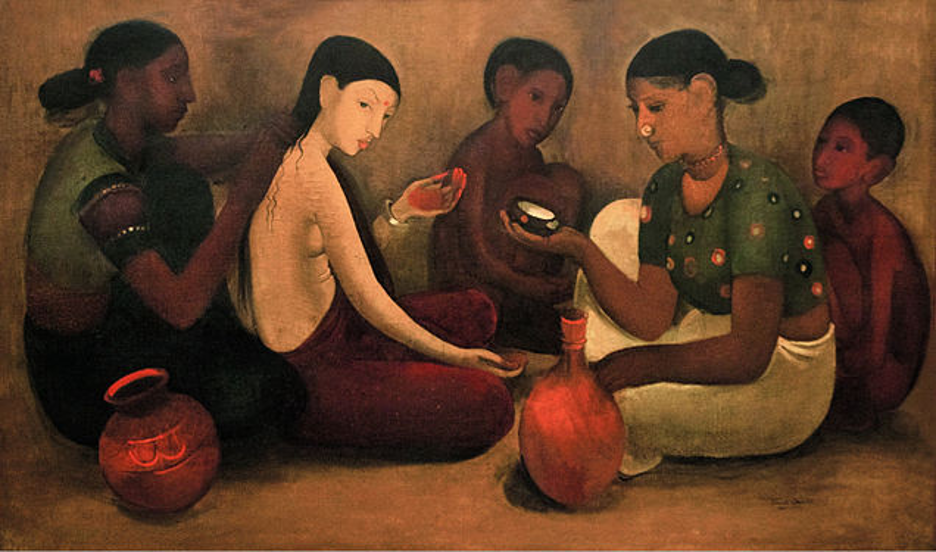

Such resolution and ethos, like Nochlin, is required, if one were to take the task of attributing female artists of Pakistan and put them under the limelight which they rightfully deserve. With talks with a local art historian, Dr. Prof. Kanwal Khalid (also a woman), a few names came up, which paved the way for other Pakistani women who aspire to become artists in this androcentric society. First and foremost is the name of Amrita Sher-Gil (1913- 1941), who has been called one of the greatest avant-garde painters of the 20th century and a pioneer in Indian painting (Wikipedia), even though the artist of her stature was not immune to the hardships she faces as a woman. She came to India for the first time in 1921 and remained there sporadically till her death. She was trained in painting in Paris and traveled throughout her life. She was devastated to see the art scene in India as the art schools all across the subcontinent still adhered to the Indo-Persian Miniature painting. She tried her utmost best to introduce modernism in Indian art.

Amrita Sher-Gil, Bride’s Toilet, 1937.

National Gallery of Modern Art

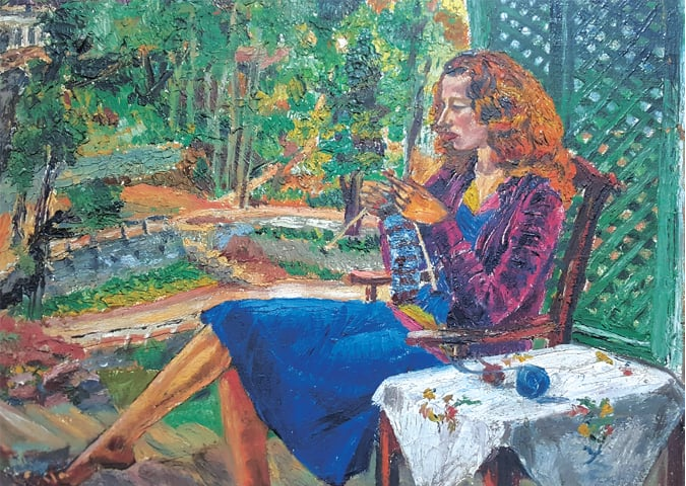

Anna Molka Ahmed (1917-1994) was a force to be reckoned with when it came to the women artists of Pakistan. Though she was not a Pakistani by birth, she did more for this country and its women than any other native artist, both men and women. She inaugurated the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Punjab, Lahore in 1940, which accepted only women in its nascent phase, not because a woman headed the department, but because the then Vice-Chancellor of the University didn't want women to take an interest in more “serious” subjects, such as Physics and Chemistry (Hashmi, 1997). Molka worked with oil paints depicting scenes of nature and still life to portraits in an expressionist manner. Her painting was heavily influenced by her European background.

Anna Molka Ahmed, Girl In The Garden

Speaking of Molka, it's sinful to forget the contributions of Zubeida Agha (1922-1997), who was also the former’s contemporary. She is considered the pioneer of non-pictorial art in Pakistan. Trained both in Pakistan and Europe, her work reflects this amalgamation of different cultures and ideologies through her depiction of color not only as a medium but its philosophical essence as well, says Khalid.

Dr. Khalid also mentioned Sughra Rababi (1922–1994), who was more of an all-rounder when it came to her artistic practice. Her artworks included paintings, calligraphy, sculptures and designs. She created her distinctive abstract style and also worked as a humanitarian for UNESCO from the proceedings of the sale of her artworks.

Left: Agha in her studio, unknown year.

Right: Sughra Rababi, Self Portrait, Oil on board, 1957.

Laila Shahzada (1926-1994) was born and trained in the field of art in England. Later she moved to Pakistan for further art training. She chose to honor the past of Pakistan by depicting the heritage of the Indus Valley Civilization in her paintings in a Western style.

In her 1997 essay, An Intelligent Rebellion: Women Artists of Pakistan, Salima Hashmi who is also a pioneer woman artist in Pakistan mentioned several “forgotten” women artists of the country and their diligence as working professionals and art educationists in our patriarchal society, especially in the turbulent times under the regime of Gen. Zia-ul-Haq, when the voices of Pakistani women were suppressed in every field. Emerging from there was quite a feat for the women artists of Pakistan as in recent years, this country has produced remarkable women artists, such as the likes of Shazia Sikander, Huma Mulji and Bani Abidi to name only a few.

Shahzada’s work, exhibited in New York City in 1955.

The recent empowerment of women has come with its unfavorable impressions as well. Now a working professional woman is considered to excel both at home and in her career while men are only to focus on their professional lives. Nevertheless, women are still struggling to fight for equity though they have not yet achieved equality. This bias has existed since the dawn of time, as the famous figurine of Venus of Willendorf is now questioned by historians and critics as to have been made by a woman looking down on her body as opposed to the preconceived notion that every great achievement has been attributed to the man.